Editor’s Note: Dr. Rebecca Chopp ’74 will be the keynote speaker at April 20’s Scholarship Gala. Learn more at www.kwu.edu/gala2024.

Bemoaning an unhappy fate is not for Rebecca Chopp ’74.

The results of a classical, liberal arts education is coming to her aid and helping to put her monsters in their place. The biggest monster is named “Alzheimer’s.”

In Greek mythology, Perseus used gifts from the gods to slay the gorgon Medusa. Chopp sees orders from her doctors as the gifts of exercise, nutrition, creativity and sleep to keep memory loss at bay.

By any measure, Chopp was one of the top educators in the country, the first female chancellor of the University of Denver (DU). Before that, she was the first female president of both Colgate University and Swarthmore College and held leadership positions at Emory and Yale universities.

Chopp has had a number of careers: ordained Methodist minister, professor of theology, scholar and author, besides university administrator. Her latest career is Alzheimer’s advocate and activist. That quest was thrust upon her when she was diagnosed with mild cognitive disorder (MCI) and the early stages of Alzheimer’s in March 2019.

“When I was diagnosed, it was very depressing, very scary,” Chopp said. “My mother and both grandmothers had dementia. Each had different types; they were all scary to me.”

The diagnosis forced her retirement from DU in 2019 at age 67, after five years as chancellor. The stress of such a high-profile job was detrimental.

She and her husband, Fred Thibodeau, mourned what the loss of a mind like hers could mean for maybe a year, year and a half. Then she did what Rebecca Sue Chopp always does when faced with a problem: She researched it and faced it head on.

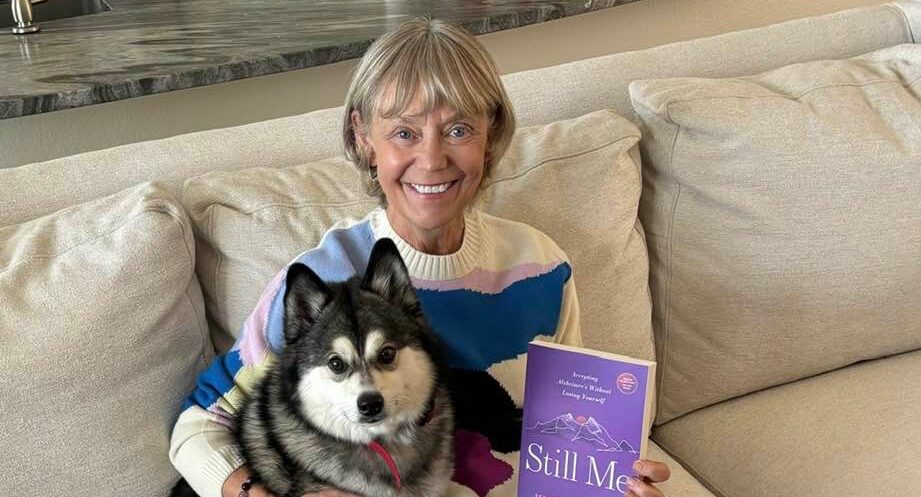

She’s put the results of that research into her latest book, Still Me: Accepting Alzheimer’s Without Losing Yourself, published in February.

“You may not have realized you were reading a book about the liberal arts, but I think this book is the most important act of a life and career dedicated to the liberal arts,” Chopp writes in Still Me.

Growing up in Salina instilled habits and attitudes early on in that life, mindsets that have served her well. Her family lived in town but also farmed — the best of both worlds, going between town and farm, she said.

“I think there is something to the Midwest, being raised in that rural life, that you just have to accept what life gives you,” she said, such as the weather.

She learned that from listening to her farmer grandfather talk about the weather and its effect on crops.

Her father, too, and his “enormous work ethic” was an inspiration.

“My father, especially, was a man who, you had to seize an opportunity,” she said. “He had no education in terms of college, but he built a couple of small companies, and he always knew how to see around a corner, see an opportunity and grab it.”

He would get up in the middle of the night, she said, and work. She often got up with him and read or worked on her own projects. That established a habit of sleeping only four or five hours a night. It enabled her to add about 20 hours of work to every week, although now she’s not so sure it was her best idea. Research has shown a link between lack of sleep and Alzheimer’s, and Chopp now gets about 12 hours of rest a day.

Her liberal arts education is fundamental to her, besides providing mythological role models. She sees all her careers as promoting the liberal arts, considering herself a teacher even while an administrator.

“For me, education was so enlarging, and I loved the liberal arts education I got at Kansas Wesleyan,” she said. “I devoted much of my life to liberal education. It’s not only about job skills, it’s also about the perspectives you learn in sociology and anthropology about human beings, what you learn in religion about what drives people, the perspective you learn in psychology. I really think, for me, helping others get a basic liberal arts education has been a huge driver.”

“As an educator, I have had great teachers, from first grade on,” she said.

She took Latin in eighth grade. She checked out all the books on spirituality, western and eastern, she could find in the library.

Although her family wasn’t religious, “I was always interested in religion and spirituality,” she said.

When her minister at First United Methodist Church, Everett Mitchell, suggested she go to Kansas Wesleyan to study religion, “I thought it was a fabulous idea!” she said.

He had some scholarship money to get her started, but her parents weren’t supportive.

“My parents at that age and place really saw me as getting married and having a bunch of kids, which would have been wonderful,” she said. “Nothing wrong with that.”

But it wasn’t for her.

“I took my first class on environmentalism and religion with Wes Jackson and Wayne Montgomery in January 1972,” Chopp said. “I was just enthralled. There was earth, farm, land, care for that, religion, Hebrew scriptures. I just jumped fully into Kansas Wesleyan.”

She was very, very busy, with a double major — religion and speech — living off-campus and often working two jobs.

“Everyone was just so supportive. I had never thought of myself as particularly smart. By the time I graduated I had a lot more confidence,” she said.

She graduated magna cum laude, spending her senior year at St. Paul Seminary in Kansas City.

She was still exploring.

“I hadn’t been raised in the tradition of faith, but I felt strongly called,” Chopp said. “It was a great experience intellectually, but maybe I wasn’t quite ready.”

She married her first husband after her first year of seminary and took a break.

“Sometimes a break is so important,” she said. “When I returned, I was gung-ho.”

The Methodist Church was less gung-ho about women ministers, having first ordained them only about 20 years earlier.

Chopp was one of only two or three Methodist women clergy in Kansas at the time. She loved serving churches with her husband, but the bishop preferred advancing his career over hers.

“I probably would not have gone on my own to get a Ph.D.,” she said. “I liked serving local churches. I loved the people, I liked preaching, I liked teaching, I liked pastoral care. But the bishop said no to my career. You know what they say, when a door slams shut, another one opens.”

The door to academia swung open to the University of Chicago Divinity School, where she earned her Ph.D. and taught for several years. Then Emory University in Georgia recruited her. By then, she was divorced, with a son.

“After 10 years of living in cold, cold Chicago, the sunny South sounded interesting,” Chopp said, and she spent 15 years there.

She was at Yale briefly before becoming the first female president of Colgate University in 2002 and the first female president of Swarthmore College in 2009.

In 2014, she took the job at DU, because she wanted to live in Colorado.

She still lives in Colorado, near her son and his wife and an older sister, all of whom help her carry out her doctor’s orders.

Her neurologist told her to live with joy — confusing, at first, but she makes it possible.

She was also told to try lifestyle interventions: a Mediterranean-style diet, a couple of hours of exercise a day and something creative to do.

Hiking was a long-time interest of hers. Now, though, instead of hiking in mountains in foreign lands, she hikes with Budhy, a Pomeranian-Huskey mix, in the Rocky Mountain foothills near where she lives. Besides hiking, she has taken yoga, ballet, strength-training and kickboxing, among other activities.

To create new neural pathways in her brain, she learned to paint, with her sister. After trying several artistic styles, learning mostly through classes on Zoom, she has settled on portraits, which also helps her memory. Chopp writes about what each subject means to her, and the subject will receive the portrait and essay after her passing.

Chopp has her new career as an advocate and activist. She’s active in Alzheimer’s groups, helping to start one, Voices of Alzheimer’s, in Colorado that is just for people dealing with Alzheimer’s. She serves on boards; spoken on podcasts, such as BrainStorm, by Us Against Alzheimer’s; and filmed a TEDx talk in November about her diagnosis and living with joy.

In the four years since her diagnosis, her MCI symptoms have worsened little, she said.

The gods — like Perseus — willing, helped by her lifestyle changes, that will be the case for a long time.

Story by Jean Kozubowski